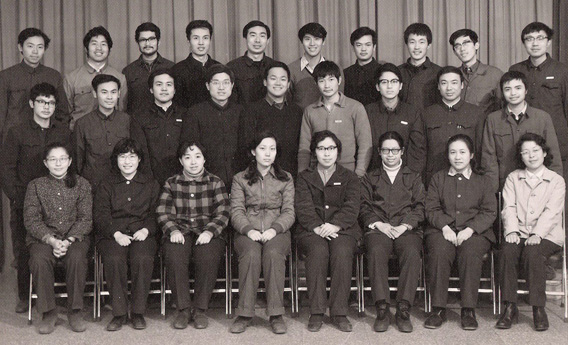

Modern Voices: Class of 1978

Focus On

As a blanket category for a diverse musical generation, China's "Class of 1978" marks not the year of graduation, but the point of entry—a heady time when educational institutions first re-opened after the decade-long lapse of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Applicants competed aggressively-not only in their immediate age group, but with 10 years' worth of candidates just coming in from the cold. Strictly speaking, as class member Liu Sola has pointed out, the students had been admitted in 1977, but the Central Conservatory of Music had to delay its opening until the next spring because of the severity of the required renovations.

Music has often thrived in adversity (just think of Stalinist Russia), but the Cultural Revolution also left a particularly significant legacy by introducing an entire generation of Chinese artists to their own people. In part through enforced "relocation" to the countryside-echoed later in mandatory fieldwork at the conservatory-the shared experiences of these educated elites for the first time embraced the range of China's expansive culture. Among their varied musical styles, the "Class of '78" perhaps shares only a single unifying principle: Whether they remained in China or relocated to the West, these composers have wholly rejected the concept of an "international" style. Theirs is a modernism inconceivable without a distinct point of origin.

Much like calligraphy, their lives have followed the same broad strokes. Each was uprooted from an urban childhood and shipped to a far-flung region of the country. Each was awakened by musical possibilities at the conservatory during a time when China itself was coming to terms with its recent past. But just as calligraphy is distinguished by a personal flourish, many of these artists developed notably distinctive voices through the particularities of their upbringing and their subsequent paths.

Tan Dun, having grown up amidst shamanistic culture in rural Hunan, discovered Western music in Beijing at the Central Conservatory and eventually became empowered by America's musical shaman, John Cage. Bright Sheng, a Shanghai native and an alumnus of that city's conservatory—the oldest institution of its kind in China—found both his voice and an entire way of musical life through Leonard Bernstein. Fellow Shanghai native and graduate of Beijing's Central Conservatory, Chen Qigang later settled in Paris, where he became the final student of Olivier Messiaen.

Through the graces of Chou Wen-chung, the composer and Columbia University professor, many of these young composers relocated to New York, where they discovered a Western compositional world newly awakening to a frame of reference outside itself. Much in the spirit of Bartók, whom each claims as a modernist ideal, these composers have found distinctive ways of expressing their cultural roots in a post-serial world, which Guangzhou-born Chen Yi likens to "thinking in Chinese, but writing in a western idiom."

The question of what makes a "Chinese composer" is no easier than determining what makes an "American composer." Nor, in our global age, are the vantage points of émigré and Chinese national so mutually exclusive. Coming to the New World once meant leaving the Old World forever. Today, as composers cross increasingly porous borders for performances and teaching positions, the line blurs between those who have brought China to the world and others (like the Sichuan-born Beijing-based Guo Wenjing) who have brought the world into a rapidly modernizing China.

From its very beginning, the "Class of '78" stirred the imagination, its unapologetic claims to free expression igniting unprecedented controversy in a country where "Serve the People" was still the reigning sentiment. But as the composers and their music have traveled throughout the world, so too has the debate. Even today, they remain at the core of a greater cultural dialogue between the influences of modernity and tradition.