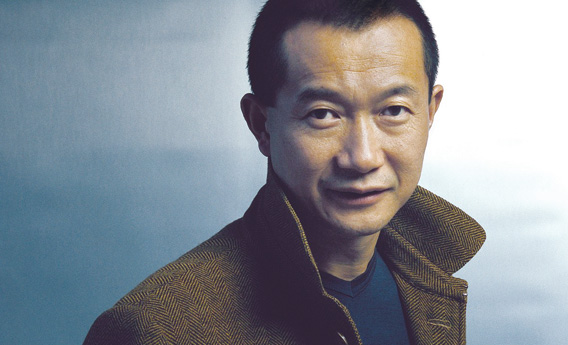

Focus On: Tan Dun

Focus On

Listen

Unlike other Chinese composers of his generation who emerged mostly from urban centers, Tan Dun never quite came in from the fields. Before Beijing’s Central Conservatory opened his ears to an entirely new musical world, Tan spent his formative years steeped in Peking Opera on one hand and in peasant ritual culture on another. As such, his work blends the avant-garde with ancient spirituality, the experimental with the theatrical, fearless innovation with crowd-pleasing populism.

It may seem incongruous to hear words like “experimental” or “spiritual” coming from someone who’s won an Oscar (as Tan did in 2001 for his score to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). In fact, few composers Chinese or otherwise have achieved such a fine balance between concert music, operatic scores, and film soundtracks. Fewer still have developed their own musical vocabulary, as Tan has done in his organic music, a broad sonic palette derived from the sounds of water, paper, and stones. For his reconciling of these worlds, we have partly to thank the great American master of incongruity, John Cage.

Few of these organic sounds are original in and of themselves, as Tan freely admits. With little provocation he will launch into memories of the Cultural Revolution, where musicians in his home village made music with whatever materials they found at hand. But after coming to New York to continue his studies at Columbia University, it was a concert of Cage’s music that reopened Tan’s ears to the sounds of his youth. “Far from home in New York City,” he recalls, “I was convinced that John Cage was my village colleague.”

In Tan Dun’s Own Words

On writing “Chinese” music:

“We were all taught to use civilized elements—the ‘good’ colors or the ‘good’ texts. But beyond this level there’s so much more—ritual culture, for example—that is perhaps even more important, because it touches everyone, not just the educated people.”

On musical life during the Cultural Revolution:

“During the Cultural Revolution, [the Party Secretary] liked our performances, so we could work in peace. There was always an enormously happy and free atmosphere. We could sing and play whatever we liked. But because of the politics of the time, our work was usually about the Revolution …”

“When we first went to conservatory, art didn’t play an important role. I was admitted to the conservatory with a piece called Dreaming of Chairman Mao … I was the first violinist in a string quartet, but I only had three strings. I played that violin for a long time. I still don’t play the fourth string very well, because I never had one for so long.”